The Last of the Anglo-Saxons

Written by Tyler Batstone

William the Conqueror in illuminated manuscript

When William the Conqueror laid claim to the throne of England in 1066 AD, it signaled the end of the Anglo-Saxon period of England. Hundreds of years of administration, culture, language, and independence were uprooted following William’s reign. What followed created medieval England as we know it, a feudal kingdom with knights, barons, serfs, and a king to govern all the classes of man. However, the Anglo-Saxons did not go quietly into the night, they raged on against the dying light of their kingdom for 10 years and bravely rebelled against William and the overlordship of the Normans. This is the story of those who resisted, fought, died, and travelled to new lands in the aftermath of the Battle of Hastings. This is how the Anglo-Saxon period of England came to a violent end.

The Norman Conquest:

When King Edward the Confessor died in 1066 AD, Duke William of Normandy laid his claim to the English throne. Edward had sworn and promised, since he had no children, that William would inherit and rule England as its king. However, Edward’s brother-in-law Harold Godwinson was crowned king of England by the Witan the day after Edward’s death, claiming that he had named Harold as his heir before his death. William, feeling cheated out of his inheritance, amassed an army to take the throne of England by force. While William and his forces landed in Southern England by the village of Pevensey, King Harald Hardrada of Norway led the last Viking invasion of England in the north near the town of Stamford. Harold rode out with his army of fyrds and housecarls to halt the invading Norsemen and defeated them at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. He quickly turned his attention to the south after hearing news of William’s landing and rode to meet the Norman army without stopping for reinforcements. On Saturday 14 October 1066 AD, the two forces fought each other on the slopes of Hastings where the Norman cavalry proved to be very efficient against the ground forces of the English. They won the day after Harold died on the battlefield and his troops were demoralized after their nobles fled the scene of the battle. After the battle, William continued marching his army to London while many of the remaining English nobles pledged their support to Edgar Aetheling of House Cerdic. As William began to travel nearer and nearer to London, many lost their resolve and he was crowned king of England on 25 December 1066 AD at Westminster Abbey. The body of Harold Godwinson was either buried by the Normans after refusing to return him to his mother Gytha Thorkelsdóttir or by his love, Edith Swanneck. Harold’s mother fled to South-western England with his sons Godwin, Edmund, and Magnus where they could stage a rebellion against the killers and usurpers of their father and restore Anglo-Saxon rule in England.

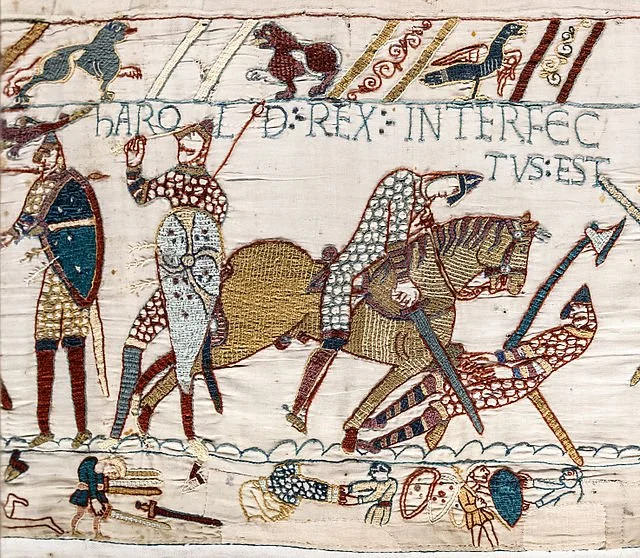

The Norman Conquest on The Bayeux Tapestry

Rebellion & Resistance:

In 1067 AD, one year after the conquest, the ealdormen of Kent along with the Norman lord, Eustace II, Count of Boulogne, led a revolt against the Normans and attempted to lay siege to a castle. Eustace was dissatisfied with the lands and titles that William gave him compared to other Norman lords and sought to take Dover castle, arming the locals of Kent and utilizing his own household guards for the attack. However, his knights were easily repelled by the castle’s garrison and the rest of the rebel forces quickly retreated. That same year, Thegn Eadric of Shropshire, allied with King Bleddyn ap Cynfyn of Gwynedd and King Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn of Powys attacked the Norman castle positioned in Hereford. They laid siege to the castle but were repelled by its Norman defenders. Hearing about these attempts of rebellion, William returned to England from Normandy to address these conflicts and to secure his hold on the kingdom.

In 1068 AD, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir and her grandsons Godwin, Edmund, and Magnus, sons of the late King Harold Godwinson, gathered allies and fortified their forces with support from Ireland. In response to this and rumors of unpaid taxes, William marched his army to the city while sacking and burning the towns and villages he believed were in support of the Godwinson family. Gytha was at Exeter when William arrived outside of its walls--her grandsons were traveling back to England with their Irish forces. At some point before the Normans breached the walls, Gytha along with some of her supporters fled the city on a boat down the River Exe. William’s forces breached the walls, encountering the city’s townsfolk and clergy who offered their surrender and pleaded for mercy. William agreed and left the city untouched, prohibiting his forces from plundering and pillaging the city. In return, he demanded fealty from the city and set the tax limit on the city to be as it was before the Norman Conquest.

Gytha and her supporters rendezvoused on the Island of Flat Holm, and they all fled to Flanders under the protection of Count Baldwin VI. In 1069 AD, Earl Gospatric of Northumbria and Edgar Aetheling returned to Northumbria with their forces along with Thegn Siward Barn and killed the garrison commander Robert FitzRichard of York castle. William travelled North and defeated the rebels at York. In the aftermath, his army massacred the city’s inhabitants and built another castle at York. King Sweyn II of Denmark arrived in Northumbria and offered his support to Gospatric and Edgar in their attempt to take the castle positioned at the city of Lincoln. William once again rode out with his army and was confronted by Danish forces in Lincolnshire, whom he beat back and left them retreating across the River Humber. William then negotiated with Sweyn II to leave England, and after the Danish forces had departed, he and his army wintered at York where he effectively razed Northumbria, massacring its inhabitants and destroying its livestock during the winter season. What ensued was a winter of torture for the remaining inhabitants of the region, starvation was rampant, accounts of cannibalism were recorded, and infanticide became widespread. This event was called the Harrying of the North and effectively quelled any further attempts of rebellion in the North. At least, until the rise of the Anglo-Saxon hero, Hereward the Wake.

The Legend of Hereward the Wake:

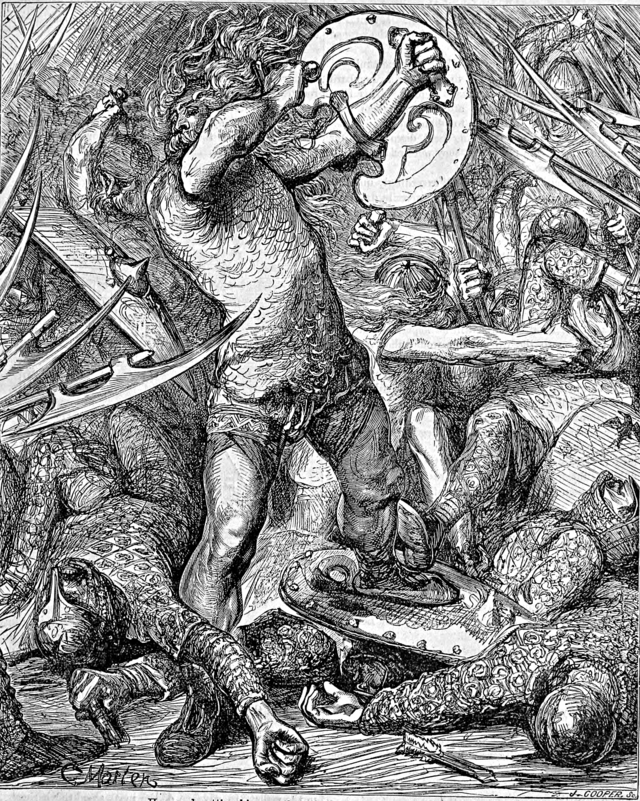

Artists depiction of Hereward fighting the Normans

The origins of Hereward the Wake have been shrouded in mystery, but it is believed that he was raised as part of the Anglo-Saxon nobility in Northumbria or Mercia. He was later exiled and declared an outlaw during the reign of Edward the Confessor. His stories abroad read like fantasies such as engaging in combat with a bear and saving a princess from an unfortunate wedding match. In 1067 AD, he returned to England to find his home overrun with Normans, and his brother was found dead with his head resting on a pike outside the house gates. He took his revenge by infiltrating a Norman feast and killed the 15 drunken knights that had murdered his brother and sacked their home. In 1070 AD, in the aftermath of the Harrying in the North, Hereward partook in the siege of Ely castle in an attempt to remove the Normans positioned there. The Isle of Ely then became the headquarters of Hereward and the other Anglo-Saxon rebels such as Earl Morcar and Earl Edwin of Mercia, however Edwin was later betrayed by his own men and killed for betraying William. Allied with the Danish king, Sweyn Ethrithson and Earl Morcar, Hereward attacked Peterborough Abbey to save the holy relics from the hands of the Normans.

When King William heard of this and the exploits of Hereward, he immediately sent an army to crush the rebellion once and for all. Hereward and Morcar retreated to the safety of Ely castle where the Normans laid siege against them but were unsuccessful in breaching the walls. They then bribed one of the monks to reveal a way into the tower which allowed them to breach the castle and win the siege. Morcar was taken as a prisoner and kept under lock and key for the remainder of his life but there are conflicting stories about the fate of Hereward the Wake. Some state that he escaped the castle and kept on raiding and rebelling against William until he received a pardon and lived in peace on the lands returned to him, another states that he was killed on the roads by Norman knights on his way to broker a peace with William.

Immigration to Byzantium & the Varangian Guard:

By 1075 AD, after a few further failed attempts at resisting Norman rule and rebelling against them, William’s grip on the kingdom was complete and there was no longer a united military effort to resist Norman rule. At this point many of the remaining Anglo-Saxons nobles were dead, imprisoned, or had their lands, titles, and influence revoked by William for their participation in a scattered rebellion that spanned almost 10 years. There is an account in the Játvarðar Saga that after King Sweyn II of Denmark could no longer promise military support in 1075 AD, many of the remaining Anglo-Saxon noble families believed that they could no longer live on the island they once called home. Led by Earl Siward of Gloucester, it is said that 350 ships departed from England carrying the Last Anglo-Saxons of England away from its shores.

Depiction of the Varangian Guard in the 11th century chronicle of John Skylitzes - Wikimedia Commons

It seemed that they did not have a clear destination in mind as the saga states that the large fleet sailed past France and landed in Ceuta, in between southern Spain and Morocco. They fought against Ceuta’s Muslims inhabitants and captured the city, before hearing that the Byzantines were being besieged by Muslim forces at Sicily. They immediately made way to Sicily and lifted the siege, providing relief to the Byzantines stationed there and driving the Muslim army back to their ships across the sea. When news of this was relayed to the Byzantine Emperor, Alexius I Komnenos, he offered to take the Anglo-Saxons into his service as part of his elite Varangian guard. Many took the emperor up on this offer, but it is said that some still wished to find a place that they could call home for themselves. The gracious Emperor then pointed out a piece of land near the Black Sea that was once under Byzantine control but had fallen to the Muslims, he granted them this land if they were able to remove the occupying force there. Those who joined the Varangian guard instantly saw combat at the Battle of Dyrrachium in 1081 AD. They fought against the Norman forces who conquered Sicily led by Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemond de Hautville.

New England:

Those who chose to settle down and build a new community of their own travelled six days until they were able to overcome the Muslim forces occupying the area and take it for themselves. Apparently, they called the land there, “England” and built towns with such names as “York” and “London” and utilized the Catholic clergy from the nearby kingdom of Hungary instead of converting to Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The Játvarðar Saga concludes the story of the last Anglo-Saxons by stating that once they were settled in, Alexius I attempted to extract taxes from them via a court official whom they later killed. It is said that the remaining Anglo-Saxons in Constantinople fled to the English colony fearing the wrath of the emperor and together, they all abandoned their newfound home and allegedly took up piracy in the area. What is known about the Anglo-Saxons who remained in the East are unknown, the Játvarðar Saga only gives us a glimpse of closure on their story. Those who stayed behind in England however, such as the peasantry, would both culturally and linguistically be transformed by Norman efforts into the cultural group known as the English in the High and Late Middle Ages and beyond.